Professor Dr. Natalia Kudriavtseva

Shorttime Fellowship

(May 2022 - August 2022)

- MA in Second/Foreign Language Pedagogy, Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine

PhD in Social Philosophy, Institute of Philosophy, National Academy of Sciences, Kyiv, Ukraine

Professor of Translation and Slavic Studies, Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, Ukraine

Fellow project: "Resistance in the occupied territories: the case of the southern city of Kherson“

Resistance is one of the integral components researched in the studies of occupation regimes. In various forms, resistance has featured prominently in the current occupation of Ukraine by the Russian Federation. Informed by the ethnographic data collected under the Russian occupation in Kherson, my project focuses on resistance in Ukraine's southern region. As a linguistic anthropologist, I concentrate on the languages of the public protests in Kherson and analyse the posters made by the protesting people and the handmade banners, and leaflets that they hung around. I also draw on the video recordings of the demonstrations and the slogans chanted by the people who took part in them. In my analysis, I aim to show how different languages that the protesters used reflect socio-cultural identities and reveal the lines of “separation and unification” constructed under the Russian occupation in Kherson. Fitting the general theme of language and identity, my project will not only provide an insight into the daily survival under occupation, but also show how identities of the so-called Russian speakers of Ukraine’s southern region are being re-shaped and re-constructed by the occupation and the war.

Results of the Fellowship

Among the pretexts for the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, as well as for the 2014 Russian aggression in Donbas and annexation of Crimea, were claims of Russian sovereignty over and protection of Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population. One of this “Russian-speaking” regions is the southern region of Kherson – the only administrative centre ever occupied by the Russian military forces. The Russian pretext for the current war grounds on simplistic equations of language and national identification which bear little resemblance to the situation on the ground.

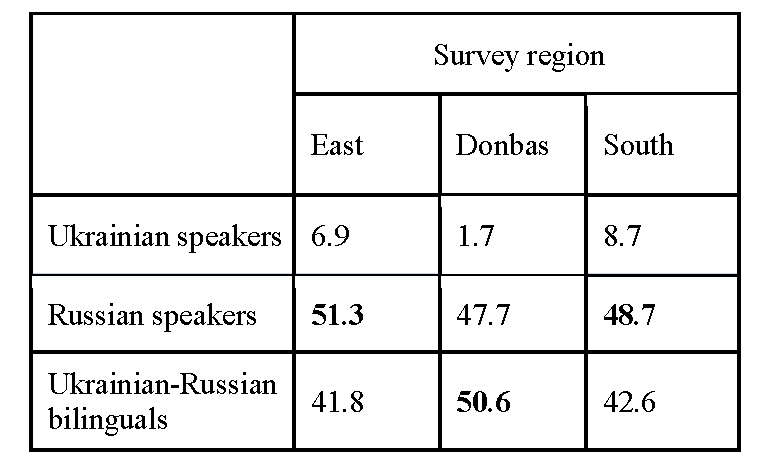

To provide insight into the actual situation, I use two sets of data which are quantitative and qualitative in nature. In the quantitative part, I draw on the results of a nationwide survey conducted in 2017 by the Sociological Association of Ukraine, i.e. before the outbreak of the full-scale Russian invasion. The novelty in the analysis of the survey data is the introduction of an additional variable for Ukrainian-Russian bilinguals, which allowed adding to the bilingual competences recognized by the respondents also those practices where both Ukrainian and Russian were actually used by them. As a result, it was possible to single out a group of respondents who were actually bilingual. This group comprised all the respondents who reported using more than one language in different communicative settings while not necessarily explicitly recognizing their own bilingualism when asked about the language they communicate in every day. The survey showed that approximately half of the population in the east and south of Ukraine used Russian (51.3% and 48.7% respectively), while the share of Ukrainian-Russian bilinguals there was also rather high: 41.8% in the east and 42.6% in the southern regions, while there were also 6.9% of Ukrainian speakers in the east and 8.7% in the south. The controlled territories of Donbas, in fact, demonstrated the highest rate of bilingual practices, with 50.6% of respondents reporting on the use of both Ukrainian and Russian in daily life. (Table 1).

These data suggest that the view of Ukraine’s southeast as ‘largely Russian-speaking’ is no longer valid: taken together, bilinguals and Ukrainian speakers comprise 48.7% in the east and 51.3% in the south, and 52.3% in Donbas. This means that around half of the whole population in Ukraine’s south-eastern regions actually already spoke Ukrainian, besides Russian, in 2017.

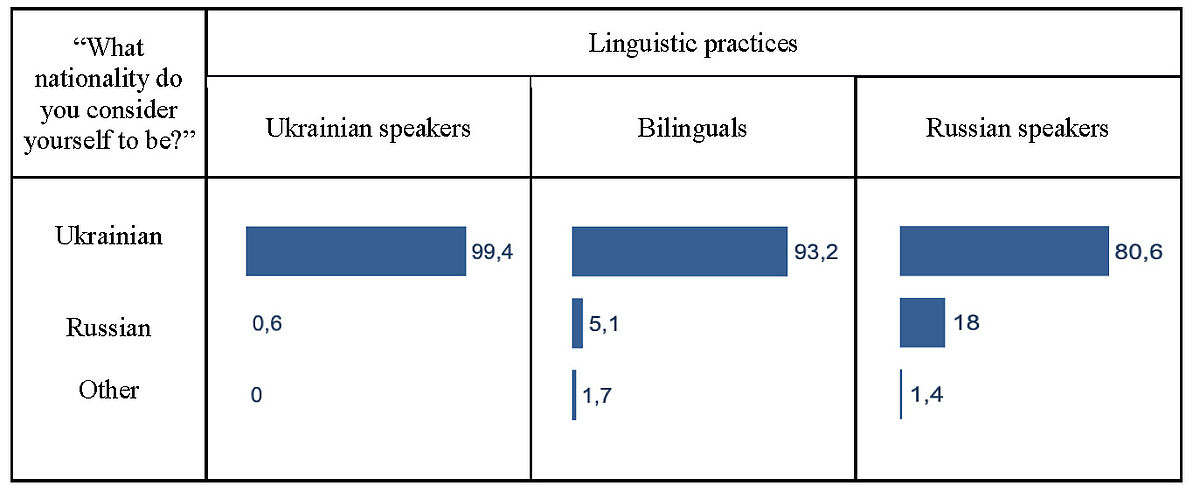

The data of the survey also showed that the majority of bilinguals all over Ukraine (93.2%) identified as Ukrainians, so did the majority of Ukraine’s Russian speakers (80.6%) (Table 2). The figures on bilingual practices in the southeast highlight the importance of the Ukrainian language there and the growing shift from Russian monolingualism towards Ukrainian-Russian bilingual practice in these parts of Ukraine.

The use of Ukrainian and Russian in Ukraine has been legitimated by different views of language, i.e. language ideologies (Woolard, Schieffelin and Kroskrity 1998; Woolard 2021). Previous studies (Søvik 2010; Kulyk 2017; Kudriavtseva 2021) drawing on nationwide and local surveys, which analysed the use of Ukrainian and Russian in Ukraine, have shown that the two languages are legitimated by different language ideologies: while Russian is perceived to be a mere means of communication, the importance of Ukrainian is both communicative and symbolic, i.e. the use of Ukrainian marks a desire to identify with the Ukrainian nation and the state. The legitimacy of the Ukrainian language derives from its status as the state language, as well as from its symbolic significance as the language of the Ukrainian nation, besides its use as an accustomed communication tool. The legitimacy of Russian stems from its use as a habitual means of communication in some domains. This finding is underscored in the current project whereby the nationwide survey showed that more than 80% of Ukraine’s Russian speakers identified as Ukrainians in 2017.

The qualitative data used in this project are interpreted on the ground of the quantitative findings and within the language ideological framework. The findings show that the Ukrainian language had been integral to the south-eastern linguistic landscape long before the full-scale Russian invasion took place in February 2022. Hence, whenever Ukrainian surfaces in Kherson protest movement, its use is not interpreted to be ad hoc, i.e. the ‘language used for this special occasion’, but customary there, considering the numbers of bilinguals residing in the south. The different views governing the use of Ukrainian and Russian – respective ideologies of identification and communication – are also expected to underpin the use of the two languages in the protest movement in Kherson.

Kherson region, which borders the annexed Crimean Peninsula in the south, has been occupied by Russian troops since the very first day of the war, and the regional centre Kherson was blocked on this same day, which made any evacuation impossible. The Russian troops attacked the city of Kherson on 1 March 2022 killing the local border guards, territorial defence, and several dozen civilians. Since the time Kherson and wider region had been trying to survive under the Russian occupation until the city was liberated by the Ukrainian Armed Forces on 11 November 2022. My family and I spent forty days in Kherson under the occupation and then were forced to leave because of the growing repressions and humanitarian crisis.

During my stay in the occupied Kherson, I managed to collect a set of ethnographic data on the protest movement as it was developing there in the March and early April of 2022. My data includes over a hundred of photographs and video recordings of the public rallies, posters and banners hung by the protesters in the city streets. The early spring of 2022 was the time when the local population was still able to openly protest against the Russian occupation and the war. Though it does not mean, of course, that, though the demonstrations were not yet dispersed, nobody was injured or later kidnapped and tortured by Russian soldiers.

The very first spontaneous protest took place on 2 March – the next day after the Russian forces attacked and occupied the city. There were just a few people in the central square who waved Ukrainian flags directly in front of the Russian soldiers and their tanks. The next demonstration took place on the 5th of March and gathered around 2,000 people. There were in fact several protests in different districts of Kherson on that day. The major demonstration took place on the 13th of March – the day when Kherson was liberated from the German troops in 1944. This rally gathered around 5,000 people and also started on the central square with people marching to the Park of Glory and carrying a 200-metre Ukrainian flag. It is important to understand that these demonstrations were not organised by one particular person or a group of people, or anyone at all. Neither were they administered by Kherson city council or the then mayor of Kherson. In the videos of the public rallies, it can be heard how demonstrators discuss this fact – that the demonstrations did not have any specific leaders. There were announcements spread on social media – Facebook and Telegram – and people saw them and came to take part in demonstrations with their relatives and friends.

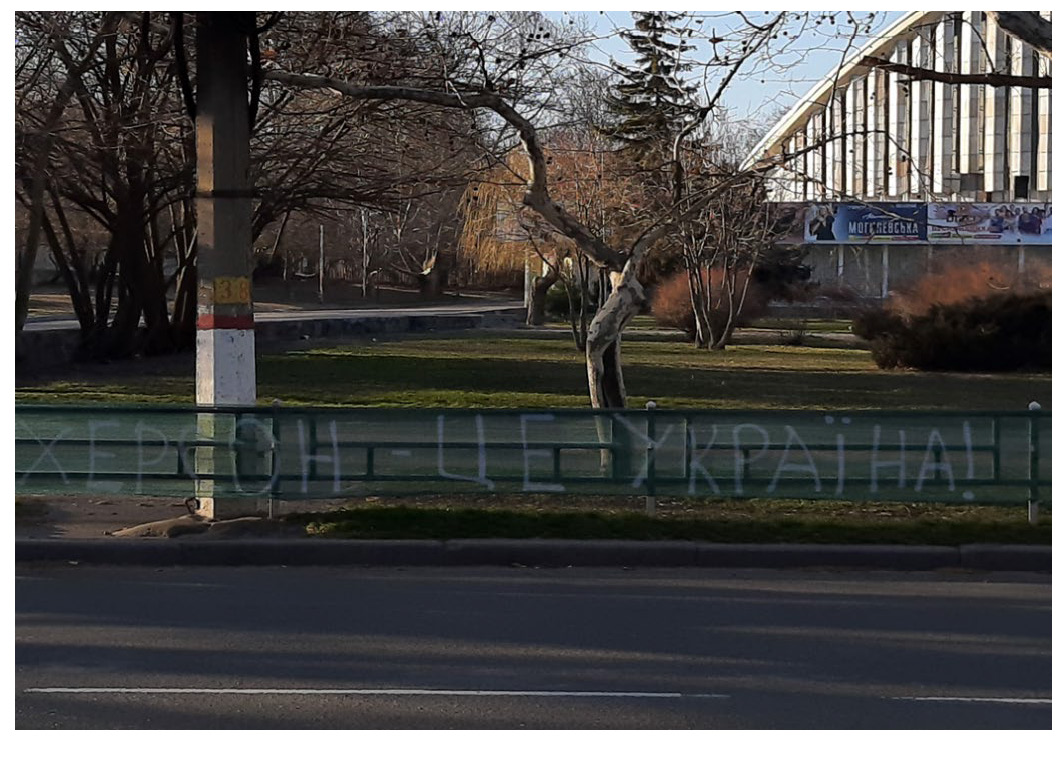

A significant factor in the protest movement was the choice of languages that the protestors used. The majority of the handmade banners were in Ukrainian (e.g. Fig. 1). The messages on them read: “Ukraine is united”, “Glory to the heroes”, “The victory is ours”, “Kherson is Ukraine”, “We will win”, “Glory to Ukraine”, “Together we stand till the victory”, “Glory to the warriors” “Glory to the Armed Forces of Ukraine”, “Thank you, everyone”, “Believe in the Armed Forces of Ukraine”, “The occupier is frightened”, “Russian Federation surrenders”, “ПТН – ПНХ” (Putin, go f@ck yourself), “Thank you, God, that I’m Ukrainian”, “United we are strong”, “Help each other”, “Crimea is Ukraine”. The majority of the posters carried by the demonstrators also were in Ukrainian and had the following messages on them: “No to phosphorus bombs”, “Close the sky over Ukraine”, “We are invincible”, “We cannot be defeated”, “We are free and independent”, “Glory to the warriors of Ukraine”, “No to Kherson People’s Republic”, “We’re Ukrainians, not Russian slaves”, “We are Ukrainians”, “Occupiers, go back home”. During the rallies, people chanted mostly in Ukrainian: “Kherson is Ukraine!”, “Glory to Ukraine!”, “Heroes don’t die, enemies die”, “Glory to the warriors of Ukrainian Armed Forces”, “Chornobaivka”, “Together we are many, we will not be defeated”.

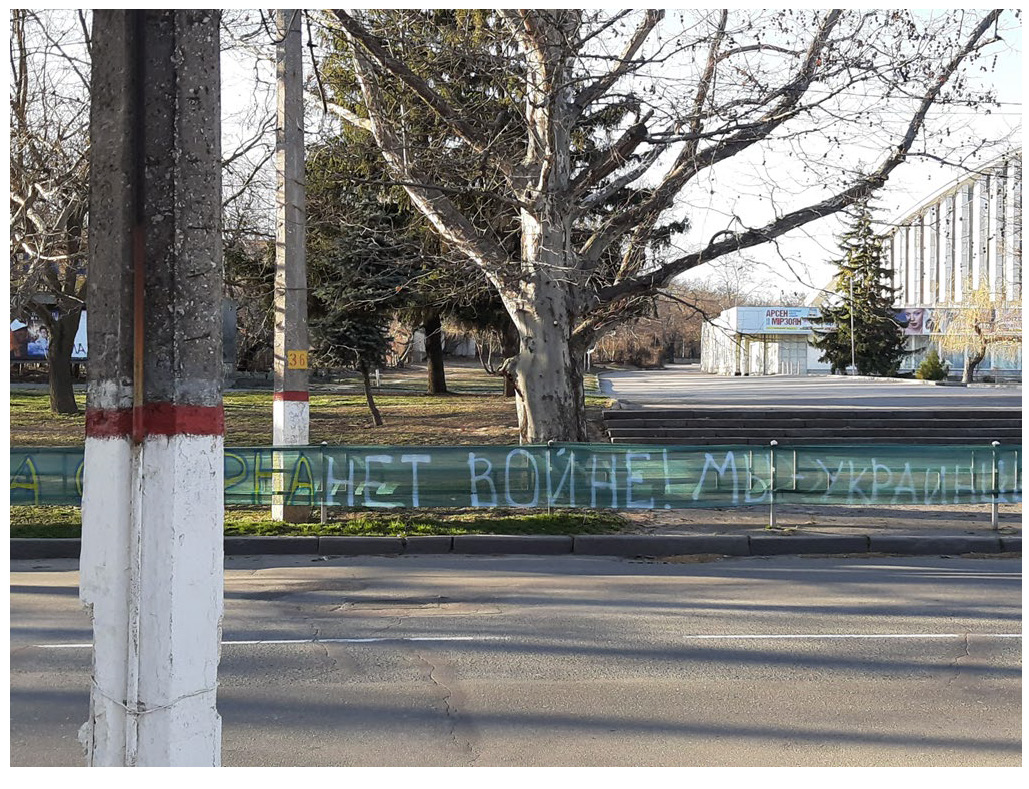

There was also occasional use of Russian on the banners and posters. The banner in Fig. 2 says “No to war!” and “We are Ukrainians!” in Russian as if translating for the Russian soldiers the meaning of all the other signs in Ukrainian so that the Russians could understand. In Liberty Square, the central square of Kherson, where the Russians established a base and posted their soldiers, the banners were hung in front of them and used Russian to communicate some stronger messages: “Go home while still alive!”, “Nobody wants you here”, “Russians, give up!” The posters in Russian said “Rascists, run home while it’s not too late”, “Kherson is Ukraine”, “Putin is a murderer”, “Russia is our enemy”. The demonstrators chanted “Fascists, out!”, “Go home!”, “Murderers!”, “Russian soldier is a fascist and occupier!”, “Shame on you!”, “Go home while still alive!” and “Occupiers!” when they passed by Russian military vehicles or when addressing the Russian soldiers posted in Liberty Square.

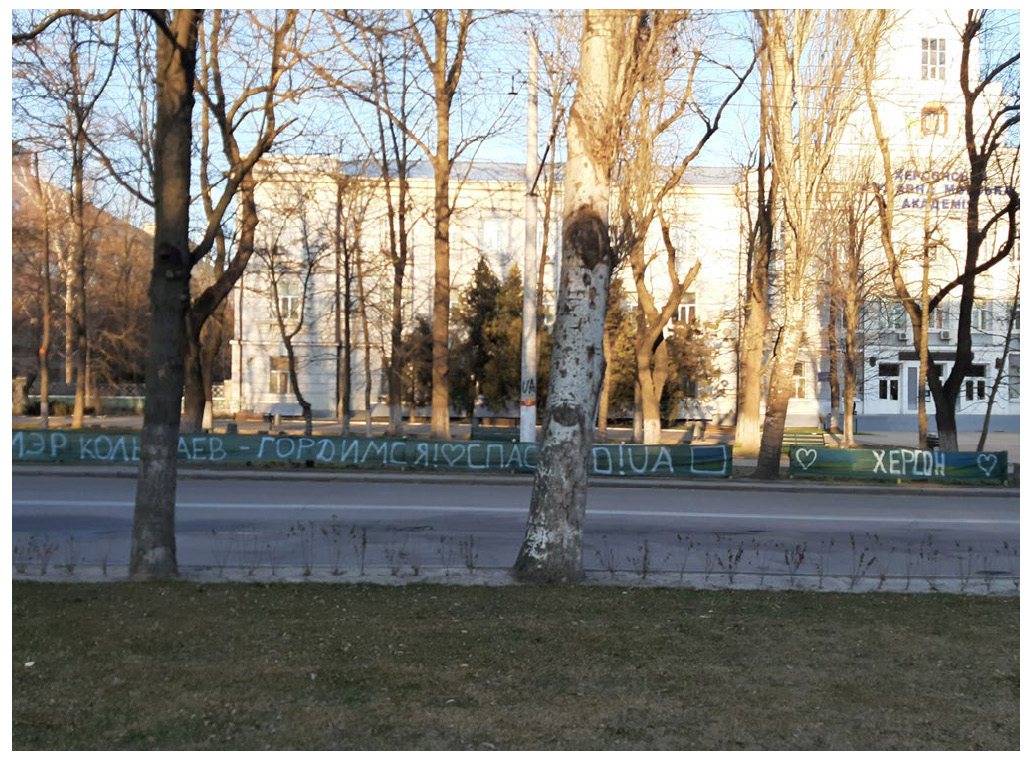

Russian was also used in the banner addressing the then mayor Ihor Kolyhaiev. This banner was hung in front of Kherson city council and read “Mayor Kolyhaiev, we are proud of you, thank you” (Fig.3).

There were also dysphemism and obscene lexis used in the posters and the chants. Among the messages written, there were the well-known “Russian warship go f@ck yourself!” and also “You’ll get f@cked, but not get Kherson”, “Occupier, go f@ck yourself”, “Putin – khuilo”. The protesters also chanted the two most famous “Russian warship go f@ck yourself!” and “Putin – khuilo”.

The language most often used in Kherson protests was Ukrainian in order to show the Russians that Kherson people were not some kind of unidentified “Russian speakers”, but Ukrainians with a distinct identity and a language of their own. The content of the messages in Ukrainian stressed the use of this language as the marker of Ukrainian national identity: Ukrainian was used to express the unity of Kherson people with other Ukrainians and the whole of Ukraine. Unlike Ukrainian, which served to express the identity of Kherson residents, Russian was used as a means of communication to convey certain messages to the Russian soldiers that occupied the town. The protesters wanted the Russians to understand how they felt about the war and occupation and used Russian, not Ukrainian, to make it clear that no one there was going to welcome Russians and greet them with flowers as those might then think. There was only one instance when Russian was used in the function of identification. But unlike Ukrainian, which served to identify nationally and express unity with the rest of Ukraine, Russian in the banner addressing the then mayor Ihor Kolyhaiev was used to identify locally, since Kherson is in part Russian-speaking as well as the mayor himself. Obscene lexis was employed as a “language of protest” against the war of Russia in Ukraine and often could not be clearly categorized as belonging to Ukrainian or Russian.

The set of qualitative data show that, in Kherson protests, Ukrainian was used to convey the messages of unification within the Ukrainian nation and separation from the russkiy mir (Russian world). Russian was mostly used to communicate with the Russian soldiers present in Kherson, with only one case of serving as a means of local identification when used to address the Russian-speaking mayor of Kherson. Obscene lexis was employed as a language of protest against the war and occupation, which is in line with earlier studies on the function of dysphemism and obscene lexis in the protests of the 2013–2014 Euromaidan (Bilaniuk 2017).

Though Kherson protesters retained Russian in use, they strongly aligned with Ukrainian in terms of their national identification. Thus, language in the protest movement functions not only as a vehicle of communicating information (Russian), but more importantly as an instrument of unification (Ukrainian), as well as protest against the occupation and the war (dysphemism).

Publications resulting from the project:

- Kudriavtseva, Natalia. (2022). Fierce Resistance in Kherson Disrupts the Russian ‘Liberation’ Scenario. Focus Ukraine, 25 May, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/fierce-resistance-kherson-disrupts-russian-liberation-scenario

- Soroka, Yuliia, Kudriavtseva, Natalia, Danylenko, Igor. Language and Social Inequalities in Ukraine: Monolingual and bilingual practices. Article under review in Ideology and Politics Journal.

References

- Bilaniuk, Laada. (2017). Purism and Pluralism: Language Use Trends in Popular Culture in Ukraine since Independence” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 35(1-4): 293–309.

- Kudriavtseva, Natalia. (2021). Standard Ukrainian in the multilingual context: language ideologies and current educational practices. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 42(2): 152–164.

- Kulyk, Volodymyr. (2017). Language attitudes in independent Ukraine: Differentiation and evolution. In The Battle for Ukrainian: A Comparative Perspective, Flier, Michael S., Graziosi, Andrea (eds.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 309–341.

- Søvik, Margarethe B. (2010). Language practices and the language situation in Kharkiv: examining the concept of legitimate language in relation to identification and utility. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 201: 5–28.

- Woolard, Kathryn A. (2021). Language ideology. In The International Encyclopaedia of Linguistic Anthropology, Stanlaw, James (ed.). Wiley Blackwell. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781118786093.iela0217 (accessed 20 July 2022)

- Woolard, Kathryn A., Schieffelin, Bambi B., Kroskrity, Paul. (1998). Language ideologies: practice and theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.